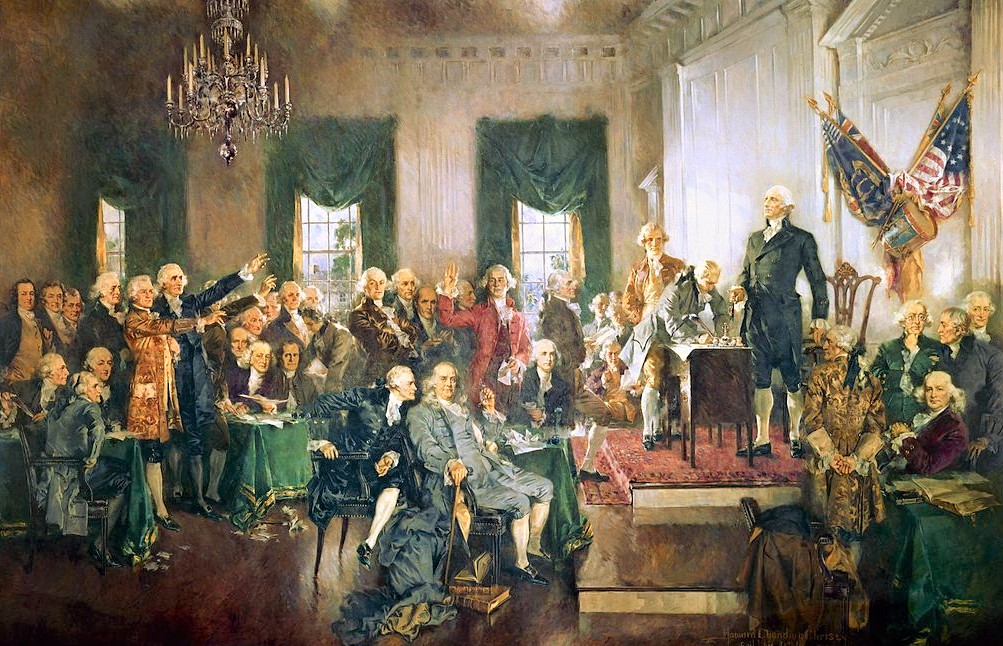

Following the American Revolution and the birthing of the United States, the American Founders undertook the task of creating a new body of laws and a new civil government for the new nation. This agreed-upon set of laws became the United States’ Constitution of 1787. Russell Kirk elaborates in his 1991 The Roots of American Order, on the meaning of a constitution: “The true constitution of any political state is not merely a piece of parchment but rather a body of fundamental laws and customs that join together the various regions and classes and interests of a country, in a political pattern that is just.” While the Declaration of Independence is an expression and agreement among Americans of the philosophical values and principles to which they adhere—the “who” and “why”—as a people and nation, the U. S. Constitution lays out a just, workable form of government and laws—the “how”—to practically order and govern the new nation according to its values and principles. The Constitution frames the United States government, provides for the country’s national security and defense, upholds justice, and protects the civil and religious liberties of the people. The Constitution is an important founding document of the American people.

While the U. S. Constitution is a practical legal document, it is based on a consensus of long-held moral, philosophical, and political beliefs, principles, and customs recognized and practiced by the American people. Some important philosophical influences on the Constitution include the colonial and state constitutions, the Great Awakening, modern Enlightenment thinkers, and the Declaration of Independence. Notably, all of these particular influences were shaped by a God-oriented worldview based on and/or consistent with the Bible. This worldview was held by colonial and founding-era Americans as well as by the political philosophers they read. In fact, the Bible itself was also a very strong, direct influence on founding-era Americans who drafted and ratified the Constitution.

The Puritans in the American colony of Connecticut drafted what is considered to be the first written constitution in the world, the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut of 1639.

The American colonial constitutions and the state constitutions in the new nation were a strong influence on the governing principles and laws of the U. S. Constitution. Drafted from 1776 to 1783, the state constitutions were themselves shaped by the colonial constitutions that preceded them. They were, as Donald Lutz explains in his 1980 essay From Covenant to Constitution in American Political Thought, the culmination of two centuries of governance and law in the American colonies and of selected European and American ideas. Particularly impactful on the state and federal constitutions were the Puritan constitutions of colonial Connecticut and Massachusetts, and the religiously tolerant colonies of Rhode Island and Pennsylvania. Many of these colonies’ laws and practices were inspired by and/or defended from the Bible. In fact, the American practice of constitutions began with the Puritans’ Bible-inspired covenantal constitutions in New England in the 1600s. As Alexis de Tocqueville observes in his 1831-1832 Democracy in America,

The general principles which are the groundwork of modern constitutions—principles which, in the seventeenth century, were imperfectly known in Europe, and not completely triumphant even in Great Britain—were all recognized and established by the laws of New England. The intervention of the people in public affairs, the free voting of taxes, the responsibility of the agents of power, personal liberty, and trial by jury, were all positively established without discussion [bold emphasis mine].

Clearly, the Puritan constitutions, in their form and content, had a conspicuous impact on America’s modern constitutions. The state constitutions which drew from the colonial constitutions, as Founder John Adams indicates in his 1778 Defense of the Constitutions of Government of the United States, were the first modern constitutions and became models for the U. S. Constitution. As such, the colonial constitutions and laws became a precedent through which the state and federal constitutions gleaned long-held American, Bible-inspired governing principles and customs.

Some important governing principles found in the Puritan colonial constitutions—the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut of 1639 and the Massachusetts Body of Liberties of 1641—that were taken up in America’s modern state and federal constitutions include popular sovereignty, consent of the governed, self-government, civil covenants, federalism, rule of law, constitutionalism, and limited government. The modern constitutions also took up religious freedom which was first attempted by religious non-conformists in the colonies of Rhode Island and Pennsylvania.

Though not distinctly political, traveling evangelist Rev. George Whitefield’s preaching during the Great Awakening had democratic elements in its style and message.

Another influence on founding-era Americans and the Constitution was the Great Awakening—the Christian evangelical revival that swept through the American colonies in the early to mid-1700s just prior to the American Revolution. Traveling evangelist George Whitefield and theologian Jonathan Edwards were the most prominent figures of this revival. Traveling evangelists’ teachings and preachings on the Bible during this period focused on spiritual life and devotion, and on spreading the Christian Gospel to all. While the revival was a religious movement, not a political one, it greatly affected American culture, society, and politics. For example, in teaching about Christ’s love and redemption for all mankind and about the individual’s choice in “born again” religious conversion, it advanced ideas of human dignity, equality, and religious tolerance. As Mark A. Noll notes in his 1992 A History of Christianity in the United States and Canada, it also had a democratic element in encouraging individuals to take an active role in their religious duties, relying less on the clergy. These ideas consequently affected Americans’ political views of democracy, freedom, and individual rights. Noll explains that this spirit of the Awakening that incorporated “a frank expression of popular democracy…had much to do with the rise of a similar spirit in politics later on.” What is more, as historians observe, the revival helped to unify colonists under a common set of basic moral and civil values, and thus to develop a stronger